Naming roads after Raila shows why Kenya is no Singapore

The Sakwa of Bondo, the clan which blessed Kenya with Raila Odinga, one of Africa’s fiercest and most enduring political leaders and statesmen, is yet to perform tero buru — the ancient Luo custom of driving bulls to cleanse the homestead of the spirit of death and mark the end of mourning.

But in the pain and anguish of national grief and, some lament, an outpouring of crocodile tears that followed, calls to immortalise the memory and sacrifices of this political giant have been strident.

Kiambu politician Moses Kuria who, for years, mocked the Luo community for not being circumcised — despite his long personal friendship with Raila — led the charge, proposing that the Technical University of Kenya, formerly the Kenya Polytechnic, be renamed in Raila’s honour.

At Raila’s burial, Homa Bay Governor Gladys Wanga went further, suggesting that the Talanta Sports Stadium, currently under construction, be named after Raila, an ardent sports lover, and that football premier league side Arsenal FC, which he supported, be invited to play against Harambe Stars to inaugurate the stadium. A mourner on social media even went so far as to suggest that (President Daniel arap) Moi’s name be scratched off a major avenue in Nairobi and be replaced with that of his old political adversary, Raila.

Befitting as the honours may be, they explain why Kenya never grew into an economic giant — like South Korea and Singapore — which, in decades past, were reportedly at par with it. For in merely naming a road, a stadium or a university after Raila, we take the downtrodden lazy, superficial path, and shun the grit and hard work required of building an enduring legacy reflective of the 80 years the man lived.

What, say, would it mean to stick engineer Raila’s name on an avenue and then crawl into bed in an unplanned, poorly governed city grappling with water shortages, insecurity, inefficient solid waste management, and a chaotic public transport system? What would it mean to stick his name on a stadium, without developing the infrastructure to identify, nurture and reward sporting talent?

Disdain for standards

What would it mean to merely rename a technical university in his name when technical training facilities are overcrowded and crippled by broken down and outdated training facilities and equipment — in the middle of a university lecturers strike when the national university education system has virtually collapsed? Of what use are the engineers we train in a country whose industrialization ground to a halt, unemployment is grinding, and major construction projects are farmed out to international firms?

These calls to rename roads and buildings after Raila, therefore, demonstrate our shortsightedness and inability, even unwillingness, to overhaul broken systems, dream big, and bring dreams to fruition. We lack the mental and personal discipline, and the tenacity and cultural mindset, to see things through; to learn from our mistakes and to build and rebuild when we should.

We, from the leadership to the led, have a disdain for standards and adhering to regulations and the rule of law. We love shortcuts, are irredeemably corrupt and embrace mediocrity like a long-lost lover. When an institution fails, we don’t fix it, we start another. When we can’t enforce a law, we enact a new one. We never saw a thief or a scoundrel we couldn’t elect, an exam we couldn’t steal, or benchmark we couldn’t ignore.

How, in the name of God, does a nation where folks stuff entire families on motorcycle taxis, willingly squeeze themselves into overloaded matatus, eat in kiosks standing beneath high voltage electricity transmission lines, and buy tomatoes on the pavements of the region’s largest metropolis, aspire to become a Singapore, a South Korea? How does a country that can’t queue without getting whipped, whose elected leaders drive on the wrong side of the road, whose police officers are serial law breakers, where voters elect the highest bidder and whose landlords build rental blocks swaying in the wind on road reserves, aspire to become a South Korea?

It would be pointless to blame the mwananchi toiling away in the sun, or the matatu driver blocking the road while honking away like a maniac. For left to their own designs, the average human child won’t bathe, change their clothing, wash hands after eating or wipe their bottoms. They won’t clean after themselves or go to school, and would rather sun themselves like salamanders, play kamari and wrestle in the yard. They wouldn’t eat vegetables and respect others without being smacked either.

Man always itches to creep back into the stone age, where survival is for the fittest, and where everything goes. He is a wild spirit whose energy must be tamed, harnessed and directed, who must be educated, forged, cultured and yoked into community and society. Ever wondered why the homes of old that raised “successful” children were dictatorships?

Kenya’s colonial legacy, upon which our early economic successes as a nation were founded, were a dictatorship: whip families out of choice farmland; force men to pay hut tax and whip them to labour on colonial farms to pay the tax; restrict rural-urban migration with a vagrancy law; whip the daylights out of children in school… abhorrent, but when the dictator departed, things fell apart.

Wabenzi

It would have been criminal and unthinkable, of course, for leaders in independent Kenya to whip the citizenry for similar reasons. But whipped we were, again and again, but only to toe the line, to turn the cheek against kleptocracy and bow to a dictatorship that existed to serve what Tanzanian scholar and politician, President Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, described as wabenzi — the political elite and their cronies defined by gleaming Mercedes Benzes, oft stolen. For long, the signature of Africa’s nouveau riche.

Our leaders could have, like Singapore founder Lee Kuan, attempted to be visionary, and emphasised “education, industrialisation, national discipline, and progress…” Instead, our education system became shambolic, churning out numbers and grades with little thought to the quality of what children learned. Our attempts at industrialisation fell apart because we couldn’t keep the lights on, or the roads open, or our hands out of the till. National discipline? Progress? How when we’ve always rewarded those who steal the national wealth meant to propel us forward?

Kenya has always cried for a strong, firm, competent leader — a non-dictator — to lead us into the nation prescribed in our anthem: where justice is our shield and defender, where we live in unity, peace and liberty, and where plenty is found within our borders. We, unfortunately, never seem capable of finding or electing that leader, and so our progress, even when we’ve dared to dream, has remained that hyena howling sarcastically in the wind

Political engineer

In mourning her husband, Raila’s widow, Ida, called him a “political engineer.” All his life, Raila fought to reimagine and reengineer Kenya’s political systems to make Kenya a just, wealthy, and equitable society defined by meritocracy and the rule of law.

Perhaps, a more fitting legacy would be to immortalize his thoughts and ideas in books, libraries, documentaries and films.

Perhaps, those thoughts and ideas, steeped in leadership, experience and history, in dreams dreamt that never were, in successes and failures, may teach us where and how we faltered, inspire us to dream anew, and trigger us to become a nation of thinkers and builders and not whinners, pickpockets and ethnic chauvinists.

Education, industrialization, national discipline, and progress have remained elusive because our leadership and politics suck. Let’s fix that, instead of sticking Raila Amolo Odinga’s name on roads, stadia and universities.

Ted Malanda is an independent journalist and former columnist and editor at The Standard.

Featured Book

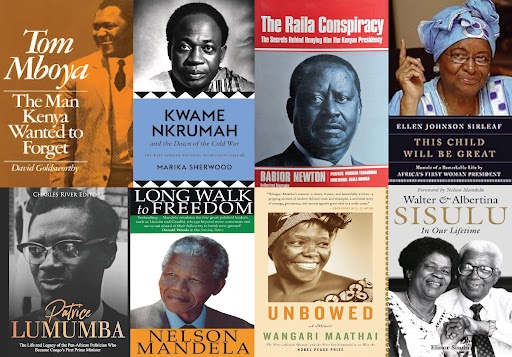

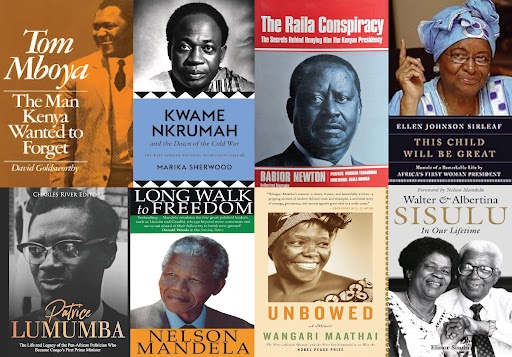

Related Book

Get to know more about the mentioned books

Related Article

Naming roads after Raila shows why Kenya is no Singapore

The Sakwa of Bondo, the clan which blessed Kenya with Raila Odinga, one of Africa’s fiercest and most enduring political leaders and statesmen, is yet to perform tero buru — the ancient Luo custom of driving bulls to cleanse the homestead of the spirit of death and mark the end of mourning.

But in the pain and anguish of national grief and, some lament, an outpouring of crocodile tears that followed, calls to immortalise the memory and sacrifices of this political giant have been strident.

Kiambu politician Moses Kuria who, for years, mocked the Luo community for not being circumcised — despite his long personal friendship with Raila — led the charge, proposing that the Technical University of Kenya, formerly the Kenya Polytechnic, be renamed in Raila’s honour.

At Raila’s burial, Homa Bay Governor Gladys Wanga went further, suggesting that the Talanta Sports Stadium, currently under construction, be named after Raila, an ardent sports lover, and that football premier league side Arsenal FC, which he supported, be invited to play against Harambe Stars to inaugurate the stadium. A mourner on social media even went so far as to suggest that (President Daniel arap) Moi’s name be scratched off a major avenue in Nairobi and be replaced with that of his old political adversary, Raila.

Befitting as the honours may be, they explain why Kenya never grew into an economic giant — like South Korea and Singapore — which, in decades past, were reportedly at par with it. For in merely naming a road, a stadium or a university after Raila, we take the downtrodden lazy, superficial path, and shun the grit and hard work required of building an enduring legacy reflective of the 80 years the man lived.

What, say, would it mean to stick engineer Raila’s name on an avenue and then crawl into bed in an unplanned, poorly governed city grappling with water shortages, insecurity, inefficient solid waste management, and a chaotic public transport system? What would it mean to stick his name on a stadium, without developing the infrastructure to identify, nurture and reward sporting talent?

Disdain for standards

What would it mean to merely rename a technical university in his name when technical training facilities are overcrowded and crippled by broken down and outdated training facilities and equipment — in the middle of a university lecturers strike when the national university education system has virtually collapsed? Of what use are the engineers we train in a country whose industrialization ground to a halt, unemployment is grinding, and major construction projects are farmed out to international firms?

These calls to rename roads and buildings after Raila, therefore, demonstrate our shortsightedness and inability, even unwillingness, to overhaul broken systems, dream big, and bring dreams to fruition. We lack the mental and personal discipline, and the tenacity and cultural mindset, to see things through; to learn from our mistakes and to build and rebuild when we should.

We, from the leadership to the led, have a disdain for standards and adhering to regulations and the rule of law. We love shortcuts, are irredeemably corrupt and embrace mediocrity like a long-lost lover. When an institution fails, we don’t fix it, we start another. When we can’t enforce a law, we enact a new one. We never saw a thief or a scoundrel we couldn’t elect, an exam we couldn’t steal, or benchmark we couldn’t ignore.

How, in the name of God, does a nation where folks stuff entire families on motorcycle taxis, willingly squeeze themselves into overloaded matatus, eat in kiosks standing beneath high voltage electricity transmission lines, and buy tomatoes on the pavements of the region’s largest metropolis, aspire to become a Singapore, a South Korea? How does a country that can’t queue without getting whipped, whose elected leaders drive on the wrong side of the road, whose police officers are serial law breakers, where voters elect the highest bidder and whose landlords build rental blocks swaying in the wind on road reserves, aspire to become a South Korea?

It would be pointless to blame the mwananchi toiling away in the sun, or the matatu driver blocking the road while honking away like a maniac. For left to their own designs, the average human child won’t bathe, change their clothing, wash hands after eating or wipe their bottoms. They won’t clean after themselves or go to school, and would rather sun themselves like salamanders, play kamari and wrestle in the yard. They wouldn’t eat vegetables and respect others without being smacked either.

Man always itches to creep back into the stone age, where survival is for the fittest, and where everything goes. He is a wild spirit whose energy must be tamed, harnessed and directed, who must be educated, forged, cultured and yoked into community and society. Ever wondered why the homes of old that raised “successful” children were dictatorships?

Kenya’s colonial legacy, upon which our early economic successes as a nation were founded, were a dictatorship: whip families out of choice farmland; force men to pay hut tax and whip them to labour on colonial farms to pay the tax; restrict rural-urban migration with a vagrancy law; whip the daylights out of children in school… abhorrent, but when the dictator departed, things fell apart.

Wabenzi

It would have been criminal and unthinkable, of course, for leaders in independent Kenya to whip the citizenry for similar reasons. But whipped we were, again and again, but only to toe the line, to turn the cheek against kleptocracy and bow to a dictatorship that existed to serve what Tanzanian scholar and politician, President Mwalimu Julius Nyerere, described as wabenzi — the political elite and their cronies defined by gleaming Mercedes Benzes, oft stolen. For long, the signature of Africa’s nouveau riche.

Our leaders could have, like Singapore founder Lee Kuan, attempted to be visionary, and emphasised “education, industrialisation, national discipline, and progress…” Instead, our education system became shambolic, churning out numbers and grades with little thought to the quality of what children learned. Our attempts at industrialisation fell apart because we couldn’t keep the lights on, or the roads open, or our hands out of the till. National discipline? Progress? How when we’ve always rewarded those who steal the national wealth meant to propel us forward?

Kenya has always cried for a strong, firm, competent leader — a non-dictator — to lead us into the nation prescribed in our anthem: where justice is our shield and defender, where we live in unity, peace and liberty, and where plenty is found within our borders. We, unfortunately, never seem capable of finding or electing that leader, and so our progress, even when we’ve dared to dream, has remained that hyena howling sarcastically in the wind

Political engineer

In mourning her husband, Raila’s widow, Ida, called him a “political engineer.” All his life, Raila fought to reimagine and reengineer Kenya’s political systems to make Kenya a just, wealthy, and equitable society defined by meritocracy and the rule of law.

Perhaps, a more fitting legacy would be to immortalize his thoughts and ideas in books, libraries, documentaries and films.

Perhaps, those thoughts and ideas, steeped in leadership, experience and history, in dreams dreamt that never were, in successes and failures, may teach us where and how we faltered, inspire us to dream anew, and trigger us to become a nation of thinkers and builders and not whinners, pickpockets and ethnic chauvinists.

Education, industrialization, national discipline, and progress have remained elusive because our leadership and politics suck. Let’s fix that, instead of sticking Raila Amolo Odinga’s name on roads, stadia and universities.

Ted Malanda is an independent journalist and former columnist and editor at The Standard.

Delete

Delete