Latest Article

Ben, you don’t have to fight to be a Maa warrior

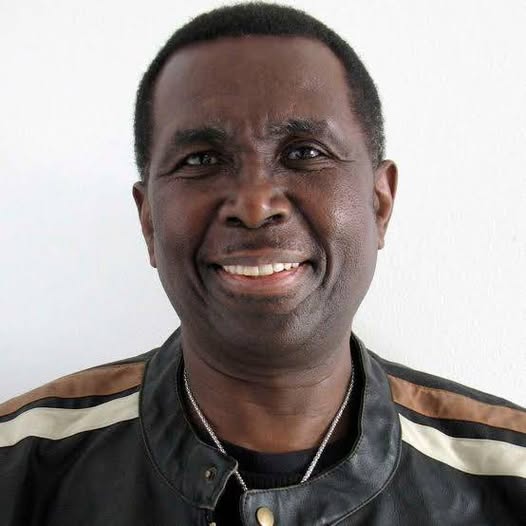

Central to this ethical inquiry is Ben’s father, a Maasai warrior, who died protecting a film crew during a lion attack. Clay avoids mythologising him. His bravery is acknowledged, but so is its cost. He exists in the narrative as both presence and absence: a figure of pride, but also of unresolved expectation. In one of the novel’s most affecting moments, Ben studies a photograph of his father in traditional Maasai dress, framed in olive wood from his village. The image becomes a powerful symbol of inherited masculinity and imagined strength. For Ben, this photograph is both an anchor and a burden. It represents an ideal he feels unable to live up to—a warriorhood defined by physical courage and sacrifice. Clay excels here in illustrating how children internalise narratives long before they understand them. Ben’s fear of returning to Kenya is not framed as weakness, but as grief: a fear of exposure, of being measured against an identity he never chose yet feels bound to honour.

Filter

This is not unique to Ruto. Across the political divide, figures such as Babu Owino regularly quote scripture, invoke divine justice and frame political struggle in spiritual terms. The Bible becomes a rhetorical shield, a way to signal moral legitimacy without submitting ideas to scrutiny. In a deeply religious society, scripture shortcuts debate, bypasses evidence and goes straight to emotion.Political theorists have long warned that when religion becomes the primary language of politics, accountability weakens. Policies are no longer judged on outcomes but on perceived righteousness. Leaders are forgiven material failure because they “fear God”. Critics are dismissed not as dissenters, but as enemies of faith.

When she first saw Scratch, she didn’t have a name. She was just a mystery cat that had eyes burning with fury or sometimes swollen with sadness. She had coal-black fur and breathed like an old man. She had appeared first outside the window, clawing hard against the slippery pane, and made eye contact with a scared Tinsy. She was barely 30 and had been moved to night shift for the first time when Scratch visited. It was impossible to scare someone like Miss Tinsy whose previous jobs had been more dreading than facing a stray cat on a cold July night in a hospital ward.

Happy are those who are afflicted here on earth for they will find comfort in heaven. You smile despite the fact that you are always in the line of fire, casting out demon after demon. And you ask them their names before ordering them out of the body. That’s what happened to you the last day you tasted alcohol. Your father had pressed this same Bible on your head and watched you lose your balance. He had asked the demon tormenting you to identify himself. Not in the same way you were asked to identify yourself at OR Tambo when you visited South Africa to preach the word. A harsh, compelling way, like you are commanding a tree to move. And the demon said a name and fled your body. You don’t remember that, you were just told. Most of these things were told to you. But there are a lot you have seen yourself.

The three boats were anchored against a log at the shore. Nobody was supposed to touch anything left in them until the next morning. Nobody slept. The whole island was awake as the devil. Prayerful men prayed. Women mourned their missing. Your mother said your dad had been so secretive the last few days before his disappearance. He had been closing himself inside his hut. Perhaps he was worrying about the tough times. We had been attacked by a belt of hyacinth and fishing was almost impossible. The lake’s clear water was now buried under green twigs and it would be so for months. He had told me over beer that he was thinking of going east. I told him to spit those words out of his mouth. He did. He never mentioned that again.

Vera’s life takes an unexpected turn when she meets Eric, a polished, seemingly successful corporate executive who embodies everything she has been taught to hope for. Their romance, laced with charm and optimism, offers Vera a glimpse into the future she has long imagined: a stable partnership, a home, and the promise of the life she believes she deserves. Yet, as Kyomuhendo reveals, appearances can be deceptive. Eric is guarding a secret of immense consequence, one that threatens to upend Vera’s plans and challenges her understanding of what she truly wants.

Beyond Kenya, Meja Mwangi carried African storytelling into global conversations, winning international recognition while remaining rooted in local realities. Even when he lived and worked abroad, his imagination never left home. Kenya was always the beating heart of his work. For generations of readers, writers, journalists and students, Mwangi offered permission: permission to write boldly, to centre the margins, to resist romanticising struggle, and to tell African stories without apology or translation.