Latest Article

Ben, you don’t have to fight to be a Maa warrior

Central to this ethical inquiry is Ben’s father, a Maasai warrior, who died protecting a film crew during a lion attack. Clay avoids mythologising him. His bravery is acknowledged, but so is its cost. He exists in the narrative as both presence and absence: a figure of pride, but also of unresolved expectation. In one of the novel’s most affecting moments, Ben studies a photograph of his father in traditional Maasai dress, framed in olive wood from his village. The image becomes a powerful symbol of inherited masculinity and imagined strength. For Ben, this photograph is both an anchor and a burden. It represents an ideal he feels unable to live up to—a warriorhood defined by physical courage and sacrifice. Clay excels here in illustrating how children internalise narratives long before they understand them. Ben’s fear of returning to Kenya is not framed as weakness, but as grief: a fear of exposure, of being measured against an identity he never chose yet feels bound to honour.

Filter

This raw, urgent poem is a confessional plunge into the fractured mind of a man drowning in guilt, poverty, lust and alcohol. Caught between the consequences of infidelity, the threat of disease, rising domestic tensions, a failing job and overwhelming shame, he turns repeatedly to the bottle as his only supposed source of courage, clarity and escape.

This raw, urgent poem is a confessional plunge into the fractured mind of a man drowning in guilt, poverty, lust and alcohol. Caught between the consequences of infidelity, the threat of disease, rising domestic tensions, a failing job and overwhelming shame, he turns repeatedly to the bottle as his only supposed source of courage, clarity and escape. Through a voice that is both tragic and darkly comic, the poem exposes the contradictions of a man who wants to “eat life full-tilt” while spiralling under the weight of his choices. It is an unfiltered portrait of urban struggle—a man wrestling with sexual recklessness, fear of AIDS, marital pressures, intrusive in-laws, financial strain, and the gnawing desire to feel powerful again. Visceral, satirical and painfully honest, this work lays bare the psychology of a man running from responsibility but haunted by every consequence. It is a portrait of survival, masculinity, and the dangerous solace of the bottle.

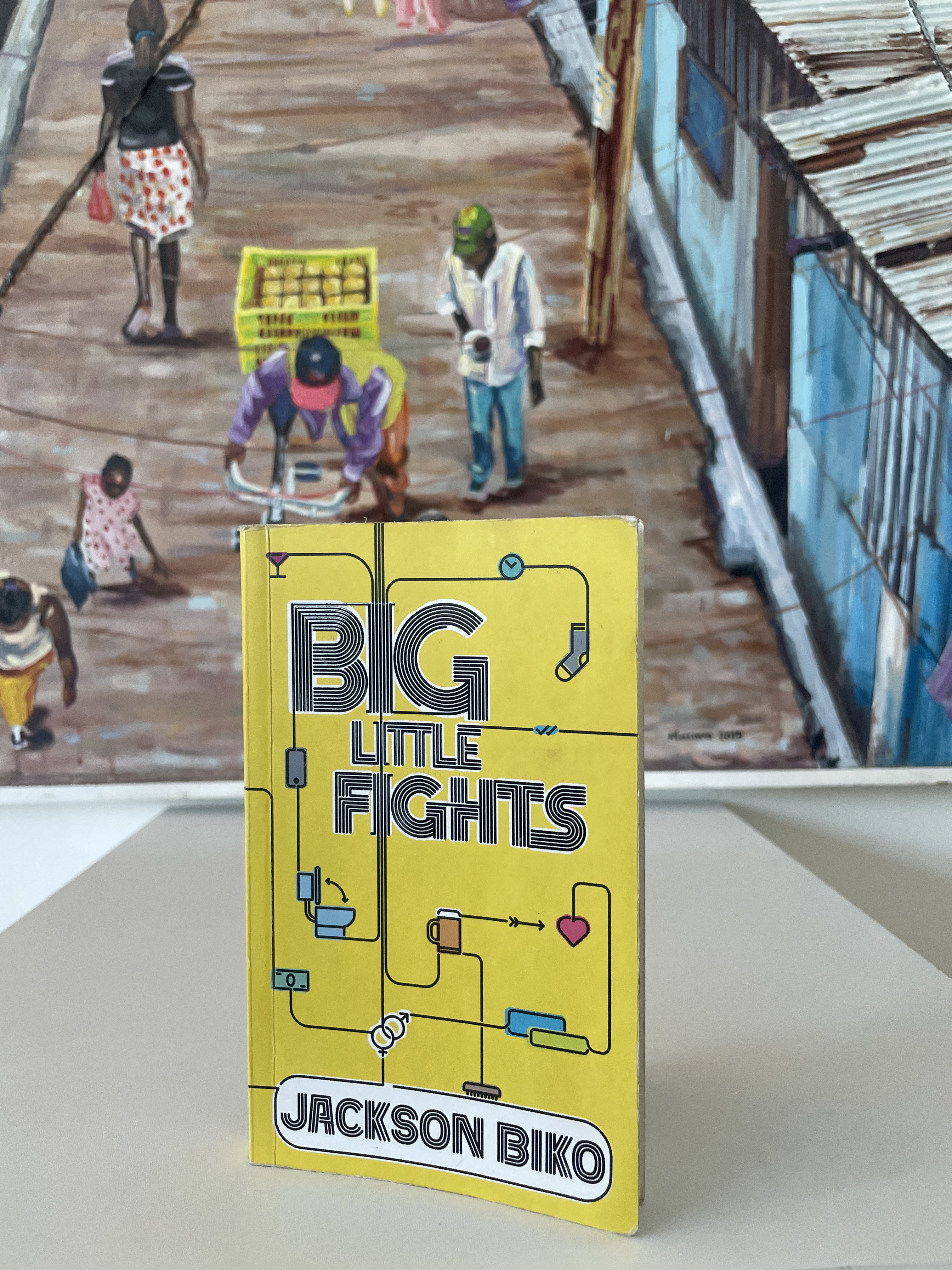

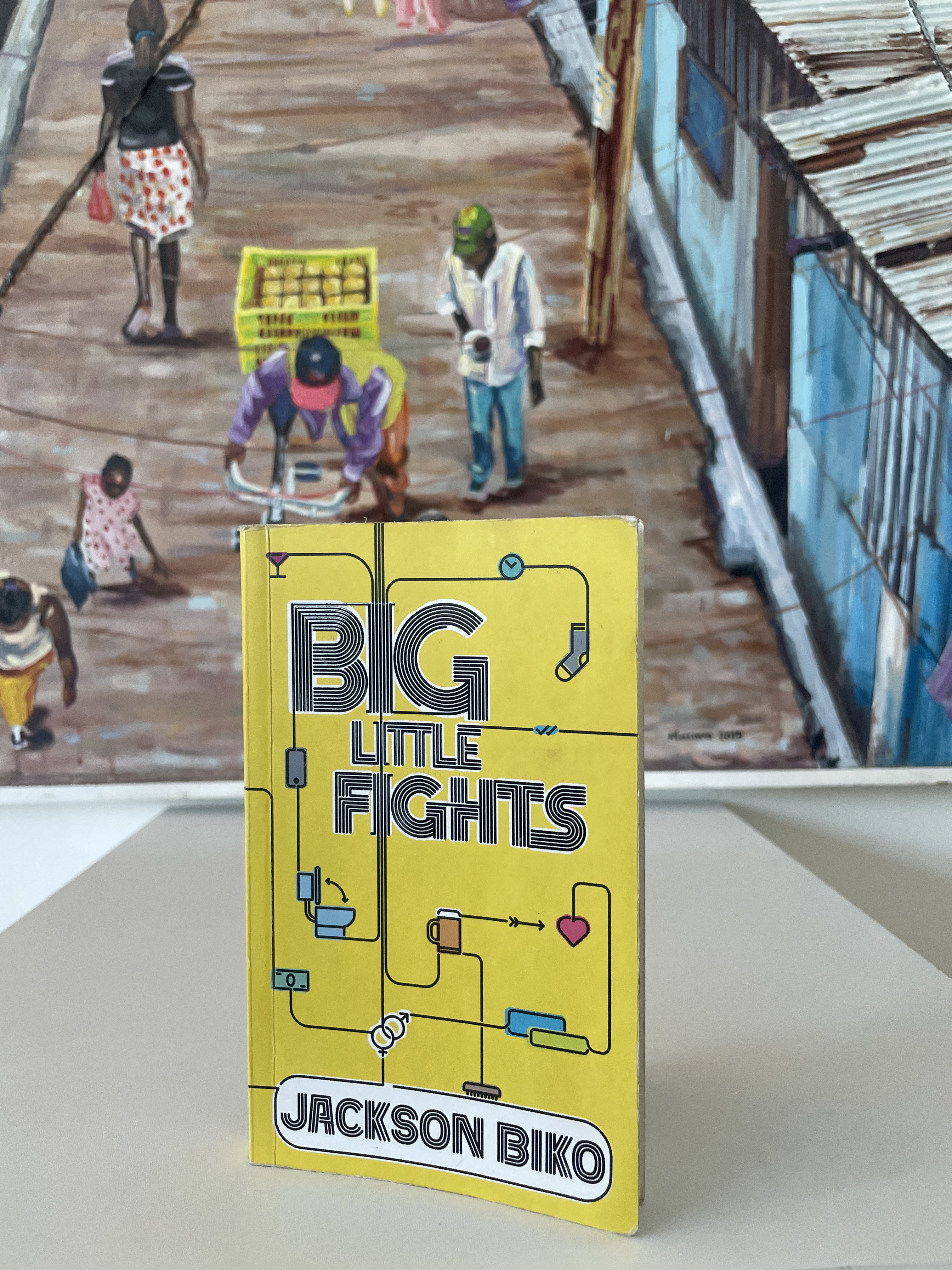

Love, as Biko shows, is messy, hilarious, frustrating, and endlessly fascinating. In a world obsessed with perfection, he reminds us that it is the small, everyday “big little fights” that reveal our priorities, insecurities, and capacity for empathy. And, if we pay attention, these tiny conflicts can teach us how to love better.

Cultural and generational tensions also permeate the book. Traditional frameworks of marriage—rooted in obedience, domesticity, and defined gender roles—clash with contemporary values of equality, independence, and self-expression. Biko demonstrates how these tensions play out in everyday disagreements, illustrating the broader societal shifts influencing modern love.

Apart from these wild musings, Aliet was surprisingly calm. The contrast between his measured presence and the provocation of his ideas perhaps explains both his devoted following and the unease he stirs in others. Walking beside him made one thing clear: Aliet’s worldview is not merely a set of opinions; it is a mirror reflecting the anxieties and contradictions of modern masculinity. Men claim supremacy yet depend on women for emotional stability; women shrink themselves to be chosen, even when the choosing devalues them; and the narratives we cling to continue to reinforce the very traps we complain about. Aliet may be controversial, but he exposes a truth that many would rather avoid: our relationships are shaped not just by love but by the power we fear losing.