TikTok, Trumpets and Deception: Unmasking Africa’s doomsday, ‘mighty’ prophets

I couldn’t help but wonder whether the widely circulated videos of Venezuela’s embattled president, Nicolás Maduro, kneeling before Kenya’s self-styled “mightiest prophet”, Dr David Owuor of the Ministry of Repentance and Holiness, were the product of artificial intelligence. In the footage, Owuor offers fervent prayers, declaring divine protection over Maduro and Venezuela, insisting that no attack would befall them. Yet reality intervened rather swiftly. The prophecies proved futile. Maduro was deposed and ended up in custody in the United States.

The spectacle felt absurd, almost surreal, but it revealed something far more familiar and far more troubling: the enduring marriage between political desperation and religious theatre. It also reignited a conversation that many Africans are now having openly—that faith, long treated as sacred and untouchable, is increasingly being interrogated for the harm it enables.

Lies of religion

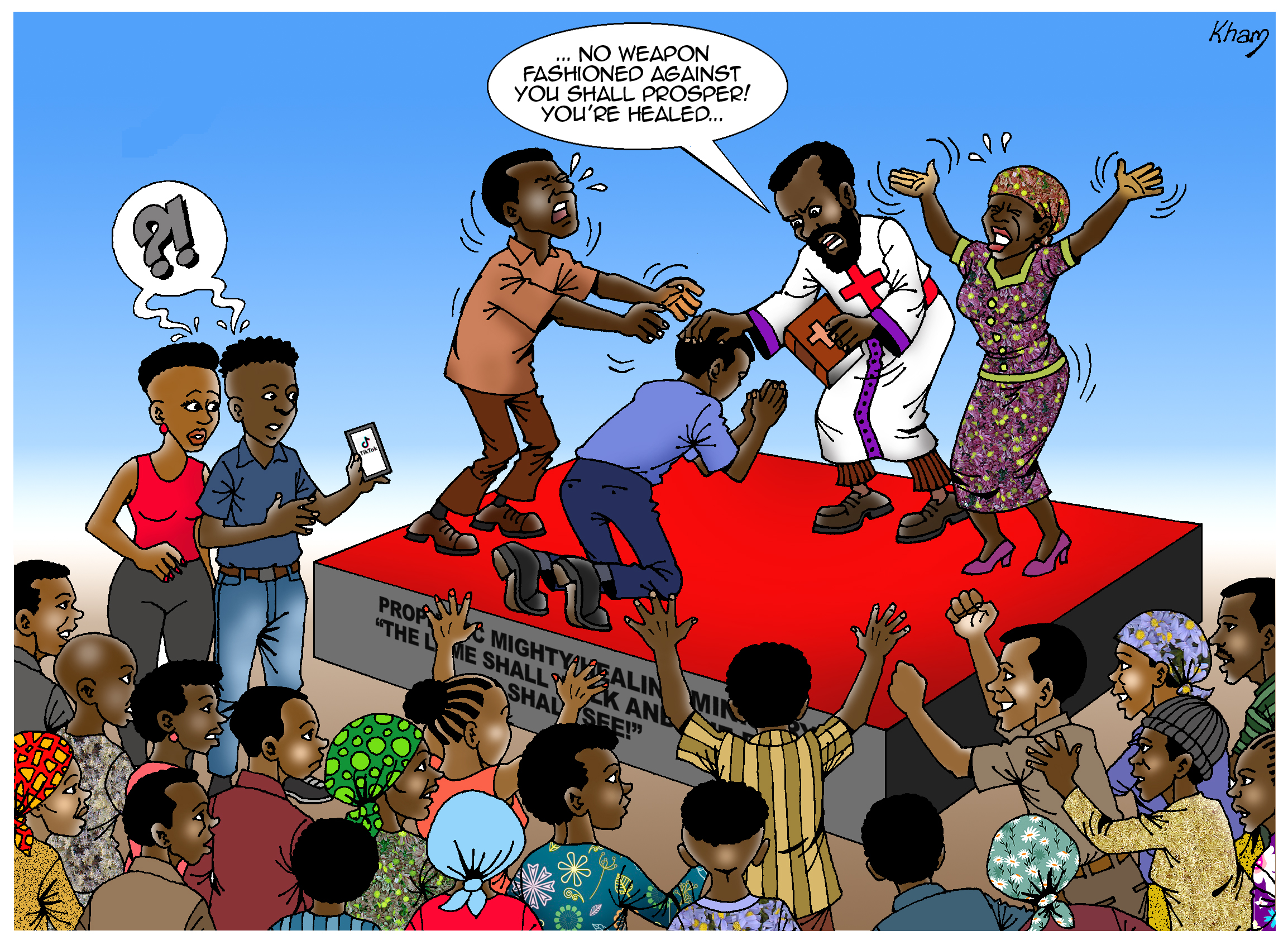

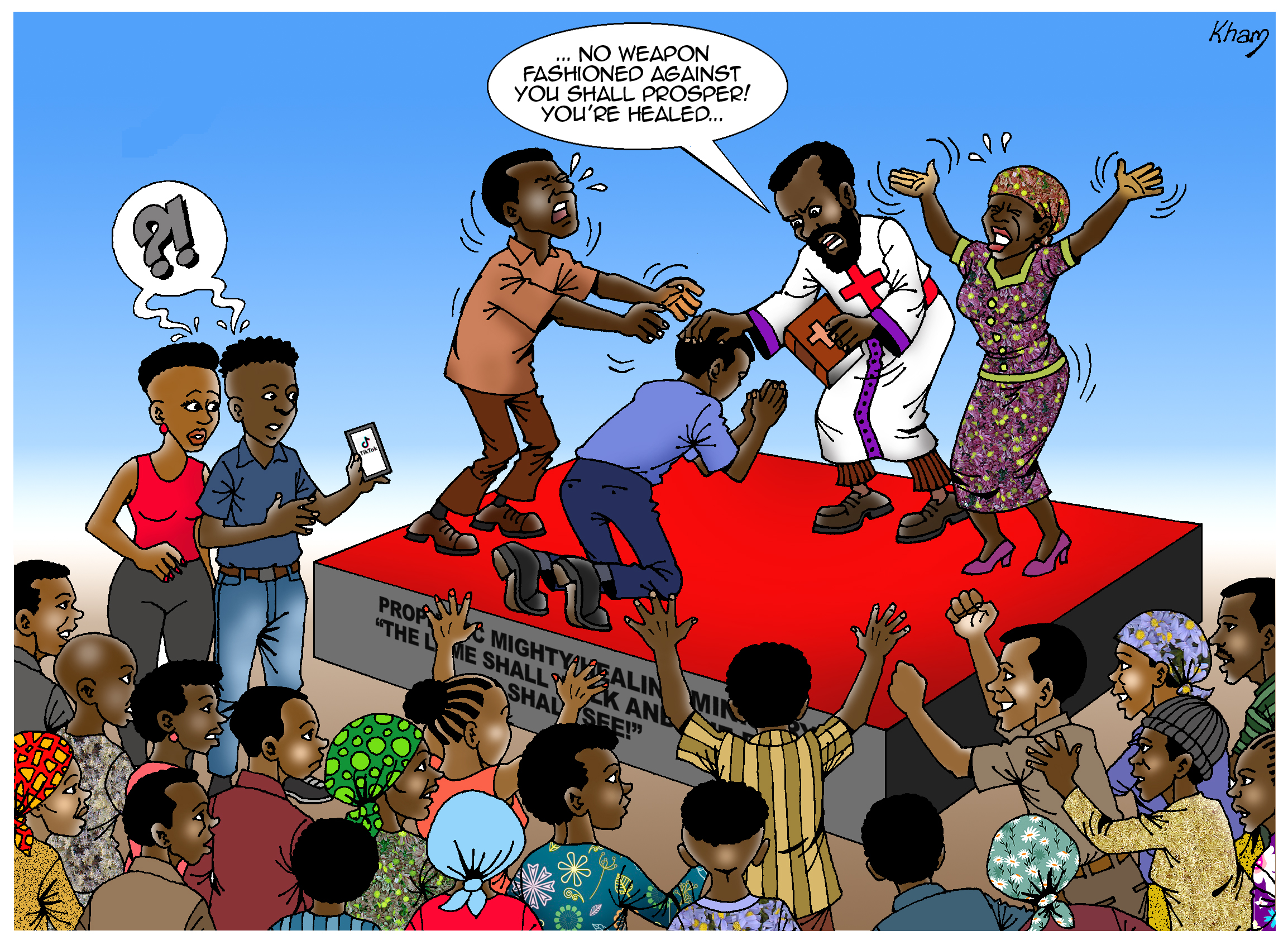

Across the continent, charismatic religion has thrived on spectacle: mass crusades, miracle claims, prophetic visions and public displays of power. But cracks are beginning to show. Increasingly, Africans are questioning not belief itself, but the authority of those who claim divine access while leaving devastation in their wake.

Philosopher Achille Mbembe, in On the Postcolony, argues that power in postcolonial societies often survives through performance rather than substance. Authority is staged and is usually theatrical. The prophet, much like the politician, governs through ritual, excess and spectacle. This helps explain why miracle crusades remain persuasive even when their promises repeatedly collapse under scrutiny.

In Kenya, the backlash against Dr Owuor’s claims of healing HIV/AIDS, cancer and other chronic illnesses in 2026 marked a significant moment. When licensed doctors and health practitioners were paraded to validate these supposed miracles, professional bodies intervened. Public health institutions warned that such claims endanger lives by encouraging people to abandon treatment. Studies by UNAIDS and the World Health Organization have long shown that faith-healing narratives around HIV/AIDS delay care, deepen stigma and directly undermine decades of public health progress.

This resistance is not anti-faith. It is anti-fraud. It signals a growing refusal to allow religion to operate without accountability simply because it cloaks itself in holiness.

Prophetic ‘performance’

The erosion of prophetic authority becomes most visible when claims tip from the unverifiable to the implausible. Dr Owuor has previously asserted that he has spoken directly with God and the archangel who is going to sound the trumpet, more remarkably, that he knows how the biblical trumpet announcing the end times will sound, with cheers from his followers. This declaration did not inspire awe so much as it invited scrutiny and satire.

Kenyan podcaster Mwafreeka, host of Iko Nini, punctured the claim with a cultural reference that resonated widely. The supposed heavenly trumpet, he suggested, sounded suspiciously like the US military taps or better the iconic 20th Century Fox movie intro: that booming, cinematic jingle etched into global pop culture. What Mwafreeka did, and what many young Africans are now doing, is refuse to suspend cultural literacy in the face of religious authority.

The danger of unregulated prophecy becomes even clearer when viewed beyond Kenya’s borders. In another widely reported case, a self-proclaimed prophet, Ebo Noah, announced that the world would end last 25 December and that God would destroy the earth through catastrophic floods. He wore sackcloth as proof of divine instruction, preached repentance and urgency on TikTok, and went as far as building physical arks to prepare his followers for salvation. Believers were instructed to sell their property, abandon their livelihoods and surrender material possessions in anticipation of the apocalypse. Many complied. When the prophesied end failed to materialise, Ebo Noah did not emerge chastened or repentant. Instead, he reappeared driving a 2025 Mercedes-Benz model—a grotesque symbol of how apocalyptic fear can be converted into private wealth.

Crucially, the state intervened. Ebo Noah was arrested on New Year’s Eve for fraud and psychological manipulation and was scheduled for a psychiatric evaluation, demonstrating that in some jurisdictions, exploiting religious fear carries legal consequences. This distinction matters not because the story is remarkable or unique, but because it is familiar. The only difference lies in consequence. In Kenya, similar figures often operate without scrutiny, fear, or sanction. What this comparison reveals is not that Africans are uniquely gullible, but that weak regulation and cultural deference to religion create ideal conditions for abuse. When prophecy is insulated from scrutiny, it mutates into a business model. When fear is sanctified, exploitation becomes righteous.

Familiar scripts, different stages

Maduro’s genuflection before a foreign prophet may seem extraordinary, but it fits a well-documented pattern across the Global South. In Latin America, particularly in Brazil and Venezuela, Pentecostal and charismatic movements have long shaped political imagination. Sociologist David Lehmann, in Struggle for the Spirit, shows how religion flourishes most aggressively in societies marked by economic instability and institutional failure. Faith becomes both refuge and weapon.

Africa’s experience mirrors this closely. Paul Gifford, in Christianity, Development and Modernity in Africa, argues that prosperity theology often redirects frustration away from structural injustice and towards supernatural solutions. When politics fails, prophets step in. When institutions crumble, miracles are offered as substitutes. Maduro’s prayers were not about belief, they were about legitimacy. And African leaders have repeatedly engaged in the same performance, seeking spiritual endorsement to shore up political weakness.

Max Weber’s theory of charismatic authority helps clarify why prophets wield such power. Charisma, Weber explains, does not rely on evidence or institutions but survives on belief. But belief is fragile—it collapses when followers collectively withdraw consent. What we are witnessing now, particularly among younger, urban Africans, is precisely that withdrawal.

Data from the Pew Research Center supports this shift. While belief in miracles remains high across sub-Saharan Africa, trust in religious leaders is declining, especially among digitally connected youth who are exposed to contradiction, failed prophecies and historical critique in real time.

Religion and politics: the opium revisited

Kenyan politicians understand something fundamental about the electorate: religion is not just belief here, it is identity. It shapes how people interpret morality, authority and destiny. And so it has become one of the most reliable tools for political mobilisation.

President William Ruto’s rise was inseparable from his overt religious performance. Campaign rallies doubled as prayer meetings. Biblical language replaced policy clarity. The image of a God-fearing leader was carefully cultivated, not incidentally, but strategically. Faith was not merely expressed, it was deployed. And it worked.

This is not unique to Ruto. Across the political divide, figures such as Babu Owino regularly quote scripture, invoke divine justice and frame political struggle in spiritual terms. The Bible becomes a rhetorical shield, a way to signal moral legitimacy without submitting ideas to scrutiny. In a deeply religious society, scripture shortcuts debate, bypasses evidence and goes straight to emotion.

Political theorists have long warned that when religion becomes the primary language of politics, accountability weakens. Policies are no longer judged on outcomes but on perceived righteousness. Leaders are forgiven material failure because they “fear God”. Critics are dismissed not as dissenters, but as enemies of faith.

History offers sobering lessons. It is not that religious leaders are inherently cruel, nor that atheism produces virtue; rather, states governed by rigid religious ideology—whether Christian, Islamic or otherwise—have often struggled with pluralism, dissent and human rights. When leaders claim divine mandate, disagreement becomes heresy. Power becomes sacred. Abuse becomes justified. A TikToker put it quite clearly: once you condition a belief, it forms identity, and identity forms groups and groups form civilizations; in the case of political factions, these defend themselves not from threat but from difference.

By contrast, secular governance, imperfect as it is, at least allows leadership to be questioned without theological consequence. A president who answers to institutions can be removed. A leader who answers to God alone cannot. This is the danger of emotional voting rooted in religious fanaticism. It produces loyalty rather than judgment, devotion rather than discernment. It rewards performance over policy, prophecy over planning.

And Kenyan politicians know this. They know that invoking God softens scrutiny. That quoting scripture signals trustworthiness even when records are thin. That faith, once stirred, can override reason.

Karl Marx’s much-quoted description of religion as “the opium of the people” is often misunderstood. Marx did not mock faith; he recognised it as a response to suffering. But opium numbs pain; it does not cure disease. In modern Africa, religion has too often been used not to confront injustice, but to anaesthetise the public against it.

TikTok and the new African spirituality

What is perhaps most fascinating is where this reckoning is taking place. Not in churches. Not in universities. But on TikTok. Spend enough time on African TikTok and a different spiritual grammar emerges. Young Africans are openly dismantling the theological violence they inherited; they’re questioning demonisation narratives, unpacking missionary Christianity, and reclaiming indigenous spiritual practices that were once labelled pagan, evil or backward.

Here, African spirituality is not mediated by a pulpit or filtered through fear. It is explained, debated and contextualised. Herbalists speak about plant medicine without promising miracles. Elders narrate cosmologies without demanding obedience. Young creators trace the lineage between African spiritual systems and modern wellness practices, exposing how much was erased and how much survived quietly.

This is not a return to blind tradition. It is a reclamation rooted in curiosity and agency. TikTok, for all its chaos, has become an archive of counter-memory. A space where Africans are unlearning the idea that spirituality must humiliate, impoverish or terrify them into submission.

Unlike charismatic Christianity, which centralises power in a single anointed figure, TikTok decentralises authority. Knowledge is communal. Claims are interrogated. Stories are stitched, corrected, contested. The algorithm, ironically, has done what institutions failed to do: it has allowed Africans to compare notes. The result is not mass atheism, but discernment.

Towards accountability

What the Maduro episode ultimately exposes is not the failure of prophecy, but the exhaustion of a model that thrives on fear, spectacle and blind obedience. Africans are not rejecting faith;they are rejecting manipulation. The faithful are no longer silent. They are asking better questions. They are listening to each other. They are remembering what was taken, distorted or demonised in the name of salvation.

And the spell, finally, is wearing off.

Tracy Ochieng is a staff writer with Books in Africa. Email: tracy.ochieng@ekitabu.com

Featured Book

.jpg)

Related Book

Get to know more about the mentioned books

Related Article

TikTok, Trumpets and Deception: Unmasking Africa’s doomsday, ‘mighty’ prophets

I couldn’t help but wonder whether the widely circulated videos of Venezuela’s embattled president, Nicolás Maduro, kneeling before Kenya’s self-styled “mightiest prophet”, Dr David Owuor of the Ministry of Repentance and Holiness, were the product of artificial intelligence. In the footage, Owuor offers fervent prayers, declaring divine protection over Maduro and Venezuela, insisting that no attack would befall them. Yet reality intervened rather swiftly. The prophecies proved futile. Maduro was deposed and ended up in custody in the United States.

The spectacle felt absurd, almost surreal, but it revealed something far more familiar and far more troubling: the enduring marriage between political desperation and religious theatre. It also reignited a conversation that many Africans are now having openly—that faith, long treated as sacred and untouchable, is increasingly being interrogated for the harm it enables.

Lies of religion

Across the continent, charismatic religion has thrived on spectacle: mass crusades, miracle claims, prophetic visions and public displays of power. But cracks are beginning to show. Increasingly, Africans are questioning not belief itself, but the authority of those who claim divine access while leaving devastation in their wake.

Philosopher Achille Mbembe, in On the Postcolony, argues that power in postcolonial societies often survives through performance rather than substance. Authority is staged and is usually theatrical. The prophet, much like the politician, governs through ritual, excess and spectacle. This helps explain why miracle crusades remain persuasive even when their promises repeatedly collapse under scrutiny.

In Kenya, the backlash against Dr Owuor’s claims of healing HIV/AIDS, cancer and other chronic illnesses in 2026 marked a significant moment. When licensed doctors and health practitioners were paraded to validate these supposed miracles, professional bodies intervened. Public health institutions warned that such claims endanger lives by encouraging people to abandon treatment. Studies by UNAIDS and the World Health Organization have long shown that faith-healing narratives around HIV/AIDS delay care, deepen stigma and directly undermine decades of public health progress.

This resistance is not anti-faith. It is anti-fraud. It signals a growing refusal to allow religion to operate without accountability simply because it cloaks itself in holiness.

Prophetic ‘performance’

The erosion of prophetic authority becomes most visible when claims tip from the unverifiable to the implausible. Dr Owuor has previously asserted that he has spoken directly with God and the archangel who is going to sound the trumpet, more remarkably, that he knows how the biblical trumpet announcing the end times will sound, with cheers from his followers. This declaration did not inspire awe so much as it invited scrutiny and satire.

Kenyan podcaster Mwafreeka, host of Iko Nini, punctured the claim with a cultural reference that resonated widely. The supposed heavenly trumpet, he suggested, sounded suspiciously like the US military taps or better the iconic 20th Century Fox movie intro: that booming, cinematic jingle etched into global pop culture. What Mwafreeka did, and what many young Africans are now doing, is refuse to suspend cultural literacy in the face of religious authority.

The danger of unregulated prophecy becomes even clearer when viewed beyond Kenya’s borders. In another widely reported case, a self-proclaimed prophet, Ebo Noah, announced that the world would end last 25 December and that God would destroy the earth through catastrophic floods. He wore sackcloth as proof of divine instruction, preached repentance and urgency on TikTok, and went as far as building physical arks to prepare his followers for salvation. Believers were instructed to sell their property, abandon their livelihoods and surrender material possessions in anticipation of the apocalypse. Many complied. When the prophesied end failed to materialise, Ebo Noah did not emerge chastened or repentant. Instead, he reappeared driving a 2025 Mercedes-Benz model—a grotesque symbol of how apocalyptic fear can be converted into private wealth.

Crucially, the state intervened. Ebo Noah was arrested on New Year’s Eve for fraud and psychological manipulation and was scheduled for a psychiatric evaluation, demonstrating that in some jurisdictions, exploiting religious fear carries legal consequences. This distinction matters not because the story is remarkable or unique, but because it is familiar. The only difference lies in consequence. In Kenya, similar figures often operate without scrutiny, fear, or sanction. What this comparison reveals is not that Africans are uniquely gullible, but that weak regulation and cultural deference to religion create ideal conditions for abuse. When prophecy is insulated from scrutiny, it mutates into a business model. When fear is sanctified, exploitation becomes righteous.

Familiar scripts, different stages

Maduro’s genuflection before a foreign prophet may seem extraordinary, but it fits a well-documented pattern across the Global South. In Latin America, particularly in Brazil and Venezuela, Pentecostal and charismatic movements have long shaped political imagination. Sociologist David Lehmann, in Struggle for the Spirit, shows how religion flourishes most aggressively in societies marked by economic instability and institutional failure. Faith becomes both refuge and weapon.

Africa’s experience mirrors this closely. Paul Gifford, in Christianity, Development and Modernity in Africa, argues that prosperity theology often redirects frustration away from structural injustice and towards supernatural solutions. When politics fails, prophets step in. When institutions crumble, miracles are offered as substitutes. Maduro’s prayers were not about belief, they were about legitimacy. And African leaders have repeatedly engaged in the same performance, seeking spiritual endorsement to shore up political weakness.

Max Weber’s theory of charismatic authority helps clarify why prophets wield such power. Charisma, Weber explains, does not rely on evidence or institutions but survives on belief. But belief is fragile—it collapses when followers collectively withdraw consent. What we are witnessing now, particularly among younger, urban Africans, is precisely that withdrawal.

Data from the Pew Research Center supports this shift. While belief in miracles remains high across sub-Saharan Africa, trust in religious leaders is declining, especially among digitally connected youth who are exposed to contradiction, failed prophecies and historical critique in real time.

Religion and politics: the opium revisited

Kenyan politicians understand something fundamental about the electorate: religion is not just belief here, it is identity. It shapes how people interpret morality, authority and destiny. And so it has become one of the most reliable tools for political mobilisation.

President William Ruto’s rise was inseparable from his overt religious performance. Campaign rallies doubled as prayer meetings. Biblical language replaced policy clarity. The image of a God-fearing leader was carefully cultivated, not incidentally, but strategically. Faith was not merely expressed, it was deployed. And it worked.

This is not unique to Ruto. Across the political divide, figures such as Babu Owino regularly quote scripture, invoke divine justice and frame political struggle in spiritual terms. The Bible becomes a rhetorical shield, a way to signal moral legitimacy without submitting ideas to scrutiny. In a deeply religious society, scripture shortcuts debate, bypasses evidence and goes straight to emotion.

Political theorists have long warned that when religion becomes the primary language of politics, accountability weakens. Policies are no longer judged on outcomes but on perceived righteousness. Leaders are forgiven material failure because they “fear God”. Critics are dismissed not as dissenters, but as enemies of faith.

History offers sobering lessons. It is not that religious leaders are inherently cruel, nor that atheism produces virtue; rather, states governed by rigid religious ideology—whether Christian, Islamic or otherwise—have often struggled with pluralism, dissent and human rights. When leaders claim divine mandate, disagreement becomes heresy. Power becomes sacred. Abuse becomes justified. A TikToker put it quite clearly: once you condition a belief, it forms identity, and identity forms groups and groups form civilizations; in the case of political factions, these defend themselves not from threat but from difference.

By contrast, secular governance, imperfect as it is, at least allows leadership to be questioned without theological consequence. A president who answers to institutions can be removed. A leader who answers to God alone cannot. This is the danger of emotional voting rooted in religious fanaticism. It produces loyalty rather than judgment, devotion rather than discernment. It rewards performance over policy, prophecy over planning.

And Kenyan politicians know this. They know that invoking God softens scrutiny. That quoting scripture signals trustworthiness even when records are thin. That faith, once stirred, can override reason.

Karl Marx’s much-quoted description of religion as “the opium of the people” is often misunderstood. Marx did not mock faith; he recognised it as a response to suffering. But opium numbs pain; it does not cure disease. In modern Africa, religion has too often been used not to confront injustice, but to anaesthetise the public against it.

TikTok and the new African spirituality

What is perhaps most fascinating is where this reckoning is taking place. Not in churches. Not in universities. But on TikTok. Spend enough time on African TikTok and a different spiritual grammar emerges. Young Africans are openly dismantling the theological violence they inherited; they’re questioning demonisation narratives, unpacking missionary Christianity, and reclaiming indigenous spiritual practices that were once labelled pagan, evil or backward.

Here, African spirituality is not mediated by a pulpit or filtered through fear. It is explained, debated and contextualised. Herbalists speak about plant medicine without promising miracles. Elders narrate cosmologies without demanding obedience. Young creators trace the lineage between African spiritual systems and modern wellness practices, exposing how much was erased and how much survived quietly.

This is not a return to blind tradition. It is a reclamation rooted in curiosity and agency. TikTok, for all its chaos, has become an archive of counter-memory. A space where Africans are unlearning the idea that spirituality must humiliate, impoverish or terrify them into submission.

Unlike charismatic Christianity, which centralises power in a single anointed figure, TikTok decentralises authority. Knowledge is communal. Claims are interrogated. Stories are stitched, corrected, contested. The algorithm, ironically, has done what institutions failed to do: it has allowed Africans to compare notes. The result is not mass atheism, but discernment.

Towards accountability

What the Maduro episode ultimately exposes is not the failure of prophecy, but the exhaustion of a model that thrives on fear, spectacle and blind obedience. Africans are not rejecting faith;they are rejecting manipulation. The faithful are no longer silent. They are asking better questions. They are listening to each other. They are remembering what was taken, distorted or demonised in the name of salvation.

And the spell, finally, is wearing off.

Tracy Ochieng is a staff writer with Books in Africa. Email: tracy.ochieng@ekitabu.com

Delete

Delete