Nobody flees from trouble better than a Kenyan

The skirmish ended as suddenly as it began. The police came, collected broken bones and issued stern warnings that were rudely ignored.

In the uneasy calm between a hazy peace and the next explosion of violence, an intrepid TV journalist wandered into the blazing heartland of Pokot County and assembled a band of warriors before the camera – lean, restless, and wild-eyed.

“Why do you fight?” the reporter posed. “Why do you and the Turkana fight?”

It is a question that has provoked colonial and “native” administrators, peacemakers and scholars of every shade for a century and counting. And now, the horse’s mouth was speaking, live on national television.

“The government is to blame,” the Pokot warrior answered, calm as an arrow swishing through the air. “They shouldn’t interfere. They should leave us to fight the Turkana in peace so that we can determine once and for all who is stronger. And then, there will be peace.”

Hah! All along, we had assumed that these clashes were about stealing goats for bride price, responding to the ravages of climate change, and other complex causes that pop up in seminars and workshops. I couldn’t help laughing at how the government always swings into action, all fury and bombast, waving a big hammer, only to hightail out of tribal dick-measuring contests screeching in pain! Hah!

When I was done laughing, I leaned back in my chair and gave it some thought, which is to say I sought more ways to laugh at the government.

Not that these skirmishes are a laughing matter. Folks and government security officers get murdered. Some are maimed for life. Household and community economies are destroyed – time and again. But then, life “out there” – in the sun-scorched arid and semi-arid lands of Kenya – has always been a wretched existence.

In Nairobi, the educated view is that pastoralists ought to know better; that they should go to school, get jobs like everyone else, and cease the archaic cultural practice of fighting over water and pasture and stealing each other’s goats. It is a laughable view, given how the “educated” class fights for “water and pasture” all the time. The only difference is we don’t have the balls to gird our loins and step into battle with the tribe perceived to be hoarding the goods. We whine incessantly in political barazas and on social media. Cluck-cluck-cluck.

Barring government “interference” and an education system designed to castrate manhood out of men, we would equally be responding to the primordial urge to smear our faces with chalk, break into war cries, and charge down the valley to pound the tribe yonder into submission.

Or would we?

Our harmless clucking and fighting while seated, I think, is born not of education or fear of the law, but of fear itself. Fear of hardship. Fear of standing ground to fight – a fear deeply ingrained in our DNA, if historical accounts are to be believed.

A history of fleeing

If you examine the history of our constellation of ethnic communities, most claim that they migrated from wherever in search of better agricultural land and to escape overcrowding. Really? There wasn’t any decent agricultural land in West-Central Africa? The Congo Forest? All along the migratory routes? And overcrowding? In the 13th century? Get a life!

I am convinced that the trigger was hostile, numerically and militarily stronger tribes beating that crap out of them. So, they lifted tails and ran. Wherever they stopped, weary and breathless, and attempted to scratch life out of the earth, they were ruthlessly whipped back onto the migration trail by resident communities – until they set foot in the geographical space called Kenya. But even here, they were careful to skirt Maasai territory for obvious reasons (wink).

It is disturbing when you think about it. At no time did the chiefs assemble their people under the shade of a humongous tree and urge them to stand up and fight against marauding invaders or hostile environments. No rousing speeches called for agricultural or military invention. Medicine men did not volunteer to engineer new concoctions to fight strange diseases decimating the children, and if they did, their efforts must have been a spectacular failure.

Instead, it was a forlorn-looking chief addressing a crestfallen people: “I don’t know what to do [sob]. Gather your goats and goatskins. We are leaving [sob].” The poor man, of course, had no idea where he was leading the people, and the people had no clue where they were headed either, but they said, “The chosen one has spoken. Twende (let’s go)!” The sole mutineer was crushed like a bug.

Kenya was thus founded by fleeing communities, and fled we have – ever since.

A failing health sector? Flee!

When our education system fails, we don’t fix it; we flee from it. When the national health insurance fund fails, we flee from it. When the police can’t fight corruption, we pay public servants better in the vain hope that this will neuter their appetite for bribes. Instead, we build appetites for softer creature comforts and hunger for bigger bribes.

If the government won’t share the national cake equitably, we flee into its arms instead of chortling it into submission. We won’t even accept that poor Kenyans need a drink more than rich people, and that we ought to manufacture safe and affordable drinks for them. Instead, we flee from the problem by chasing the poor, staggering bastards all over the hills.

It is mind-boggling that hundreds of years after fleeing hostile environments in other parts of Africa, we still flee from droughts, floods and hunger instead of standing our ground to fight. The overcrowding we fled from in the 14th century has caught up with us in our cities. But instead of confronting the challenge, we are migrating further afield, turning rich farmland into residential plots.

In our villages, when the earth can no longer feed us, we don’t think of manure, faster-growing and better-quality crops or livestock. We sell the land and buy boda boda taxis to get squashed on highways in the dark. Or sigh helplessly and migrate to overcrowded cities and the indignity of shared public toilets.

If, however, there is one redeeming character trait that we inherited from our fleeing ancestors, it is blind faith and the courage to flee into the unknown.

Any surprise that we now flee “overcrowding” at home to seek “fertile agricultural land” in war-torn countries?

Ted Malanda is an independent journalist and former columnist and editor at The Standard.

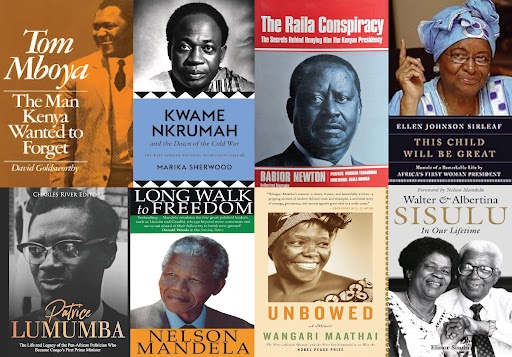

Featured Book

%20(1).jpg)

Related Book

Get to know more about the mentioned books

Nobody flees from trouble better than a Kenyan

The skirmish ended as suddenly as it began. The police came, collected broken bones and issued stern warnings that were rudely ignored.

In the uneasy calm between a hazy peace and the next explosion of violence, an intrepid TV journalist wandered into the blazing heartland of Pokot County and assembled a band of warriors before the camera – lean, restless, and wild-eyed.

“Why do you fight?” the reporter posed. “Why do you and the Turkana fight?”

It is a question that has provoked colonial and “native” administrators, peacemakers and scholars of every shade for a century and counting. And now, the horse’s mouth was speaking, live on national television.

“The government is to blame,” the Pokot warrior answered, calm as an arrow swishing through the air. “They shouldn’t interfere. They should leave us to fight the Turkana in peace so that we can determine once and for all who is stronger. And then, there will be peace.”

Hah! All along, we had assumed that these clashes were about stealing goats for bride price, responding to the ravages of climate change, and other complex causes that pop up in seminars and workshops. I couldn’t help laughing at how the government always swings into action, all fury and bombast, waving a big hammer, only to hightail out of tribal dick-measuring contests screeching in pain! Hah!

When I was done laughing, I leaned back in my chair and gave it some thought, which is to say I sought more ways to laugh at the government.

Not that these skirmishes are a laughing matter. Folks and government security officers get murdered. Some are maimed for life. Household and community economies are destroyed – time and again. But then, life “out there” – in the sun-scorched arid and semi-arid lands of Kenya – has always been a wretched existence.

In Nairobi, the educated view is that pastoralists ought to know better; that they should go to school, get jobs like everyone else, and cease the archaic cultural practice of fighting over water and pasture and stealing each other’s goats. It is a laughable view, given how the “educated” class fights for “water and pasture” all the time. The only difference is we don’t have the balls to gird our loins and step into battle with the tribe perceived to be hoarding the goods. We whine incessantly in political barazas and on social media. Cluck-cluck-cluck.

Barring government “interference” and an education system designed to castrate manhood out of men, we would equally be responding to the primordial urge to smear our faces with chalk, break into war cries, and charge down the valley to pound the tribe yonder into submission.

Or would we?

Our harmless clucking and fighting while seated, I think, is born not of education or fear of the law, but of fear itself. Fear of hardship. Fear of standing ground to fight – a fear deeply ingrained in our DNA, if historical accounts are to be believed.

A history of fleeing

If you examine the history of our constellation of ethnic communities, most claim that they migrated from wherever in search of better agricultural land and to escape overcrowding. Really? There wasn’t any decent agricultural land in West-Central Africa? The Congo Forest? All along the migratory routes? And overcrowding? In the 13th century? Get a life!

I am convinced that the trigger was hostile, numerically and militarily stronger tribes beating that crap out of them. So, they lifted tails and ran. Wherever they stopped, weary and breathless, and attempted to scratch life out of the earth, they were ruthlessly whipped back onto the migration trail by resident communities – until they set foot in the geographical space called Kenya. But even here, they were careful to skirt Maasai territory for obvious reasons (wink).

It is disturbing when you think about it. At no time did the chiefs assemble their people under the shade of a humongous tree and urge them to stand up and fight against marauding invaders or hostile environments. No rousing speeches called for agricultural or military invention. Medicine men did not volunteer to engineer new concoctions to fight strange diseases decimating the children, and if they did, their efforts must have been a spectacular failure.

Instead, it was a forlorn-looking chief addressing a crestfallen people: “I don’t know what to do [sob]. Gather your goats and goatskins. We are leaving [sob].” The poor man, of course, had no idea where he was leading the people, and the people had no clue where they were headed either, but they said, “The chosen one has spoken. Twende (let’s go)!” The sole mutineer was crushed like a bug.

Kenya was thus founded by fleeing communities, and fled we have – ever since.

A failing health sector? Flee!

When our education system fails, we don’t fix it; we flee from it. When the national health insurance fund fails, we flee from it. When the police can’t fight corruption, we pay public servants better in the vain hope that this will neuter their appetite for bribes. Instead, we build appetites for softer creature comforts and hunger for bigger bribes.

If the government won’t share the national cake equitably, we flee into its arms instead of chortling it into submission. We won’t even accept that poor Kenyans need a drink more than rich people, and that we ought to manufacture safe and affordable drinks for them. Instead, we flee from the problem by chasing the poor, staggering bastards all over the hills.

It is mind-boggling that hundreds of years after fleeing hostile environments in other parts of Africa, we still flee from droughts, floods and hunger instead of standing our ground to fight. The overcrowding we fled from in the 14th century has caught up with us in our cities. But instead of confronting the challenge, we are migrating further afield, turning rich farmland into residential plots.

In our villages, when the earth can no longer feed us, we don’t think of manure, faster-growing and better-quality crops or livestock. We sell the land and buy boda boda taxis to get squashed on highways in the dark. Or sigh helplessly and migrate to overcrowded cities and the indignity of shared public toilets.

If, however, there is one redeeming character trait that we inherited from our fleeing ancestors, it is blind faith and the courage to flee into the unknown.

Any surprise that we now flee “overcrowding” at home to seek “fertile agricultural land” in war-torn countries?

Ted Malanda is an independent journalist and former columnist and editor at The Standard.

Delete

Delete