Latest Article

Ben, you don’t have to fight to be a Maa warrior

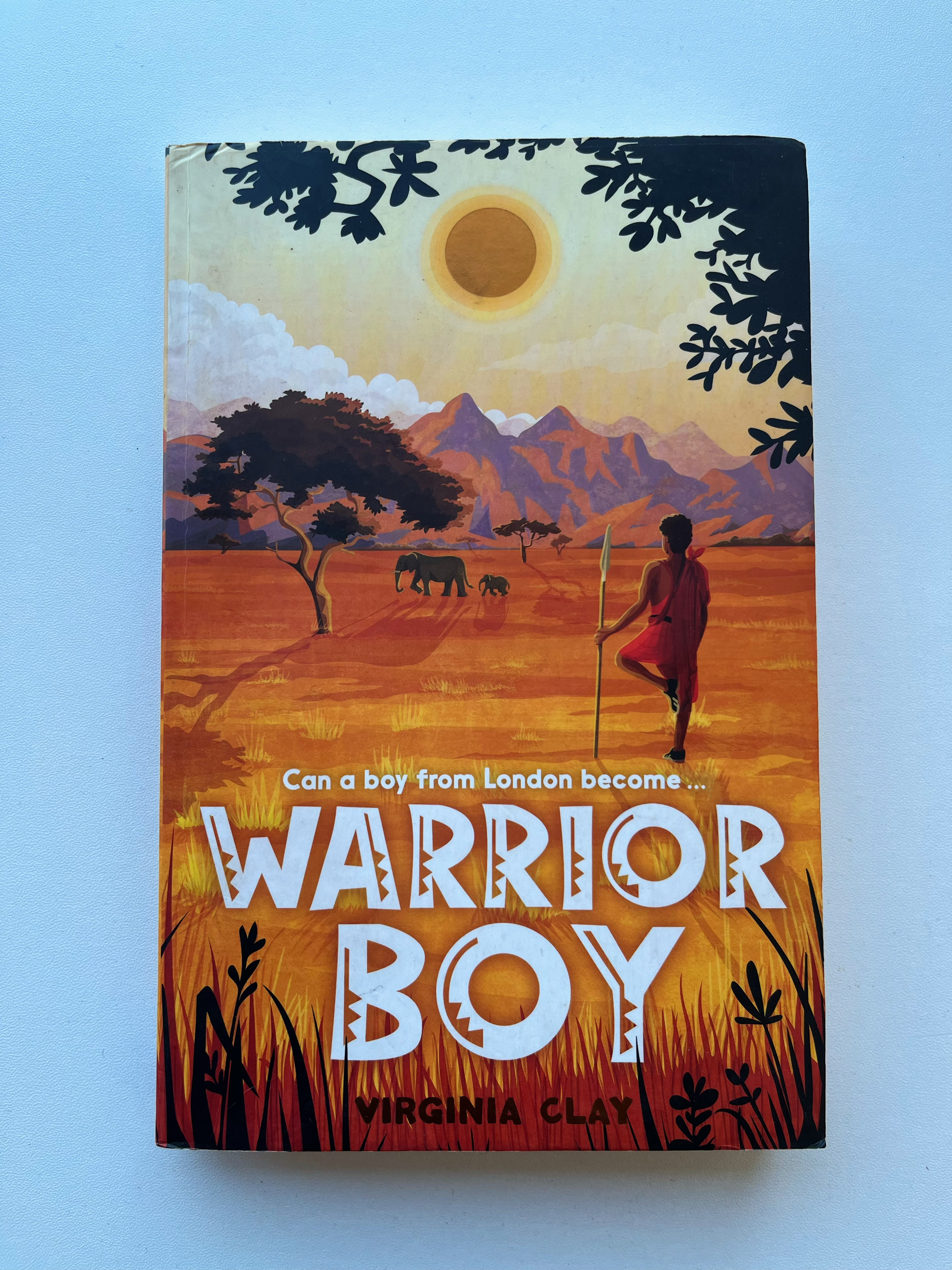

Central to this ethical inquiry is Ben’s father, a Maasai warrior, who died protecting a film crew during a lion attack. Clay avoids mythologising him. His bravery is acknowledged, but so is its cost. He exists in the narrative as both presence and absence: a figure of pride, but also of unresolved expectation. In one of the novel’s most affecting moments, Ben studies a photograph of his father in traditional Maasai dress, framed in olive wood from his village. The image becomes a powerful symbol of inherited masculinity and imagined strength. For Ben, this photograph is both an anchor and a burden. It represents an ideal he feels unable to live up to—a warriorhood defined by physical courage and sacrifice. Clay excels here in illustrating how children internalise narratives long before they understand them. Ben’s fear of returning to Kenya is not framed as weakness, but as grief: a fear of exposure, of being measured against an identity he never chose yet feels bound to honour.

Filter

Bulawayo’s win was not simply about recognition. It was about the arrival of a new voice; sharp, urgent, and unwilling to romanticise hardship. The children in Hitting Budapest are not abstract symbols of poverty; they are fully alive, funny, cruel, curious, and unforgettable.

Traditionally, the nyatiti was reserved for initiated men. For a young Japanese woman to not only learn it but master it was unthinkable.

Social media has been transformative. It’s allowing Africans to reclaim stories in real-time—whether it’s TikTokers teaching indigenous languages or Instagram creators reviving ancient textile traditions. Technology is helping bypass traditional gatekeepers, making it easier to tell our stories from our perspective.

.png)

His Only Wife by Peace Adzo Medie begins with Elikem absent on his wedding day, represented instead by his brother Richard. It is a story that peels back the curtain on marriage, family pressure, and the politics of beauty in African society.

This book is utterly charming, laugh‑out‑loud funny, and deeply moving. It portrays resilience — how children raised by grandparents in the countryside, by a nanny in the city and then at boarding school, with little parental presence, can grow up self‑reliant and perceptive. It’s a voice seldom heard in children’s literature and one that heralds a new and powerful wave of African storytelling by Africans, for Africans

Kinyatti, who was himself taken prisoner for six and a half years in 1982 for writing on the Mau Mau movement during Daniel arap Moi’s regime, intimates the hard conditions and torture prisoners faced.